Ending NYCHA’s Dependence Trap: Making Better Use of New York’s Public Housing

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) operates 174,000 total units, making it, by far, the largest public housing authority in the United States. But living conditions in NYCHA units are abysmal. After decades of deferred maintenance, necessary repairs and renovation needs are estimated to cost as much as $30 billion. In 2018, the federal government filed a complaint against the authority for failure to uphold federal health and safety regulations. Federal district judge William Pauley, in a decision that led to the appointment of a federal monitor, found that “NYCHA’s size is paralleled by its organizational disarray in providing any semblance of adequate housing for some of [society’s] most vulnerable members and its systemic cover-up of a host of fundamental health and safety issues.”[1]

But NYCHA’s shortcomings go beyond its profound maintenance failures. Rather than provide short-term aid to people trying to build their lives and gain income, its policies promote long-term dependence. NYCHA is not effectively allocating the units it currently has available, nor is it offering housing in configurations that would actually meet the needs of the 177,504 households currently on its public housing waiting list.[2] Some 32.9% of all NYCHA tenants are “over-housed”—that is, they have more bedrooms than they need. By contrast, 16% of the city’s households in poverty, which would qualify for public housing were it available, live in overcrowded conditions. Indeed, the average number of household members NYCHA-wide is only 2.2.[3] Nearly 60% of those on the authority’s waiting list qualify for a studio or a one-bedroom apartment, based on eligibility criteria such as age and gender. But those constitute only 25% of all NYCHA units. Slow turnover makes matters worse. Nearly half (47%) of households have been in their units for 20 or more years, and 18% have been there for over 40 years. The median tenure of NYCHA tenants is 19 years, far exceeding the national median of 9 years[4]—at a time when only about 5,400 apartments become available annually.

This paper suggests three new policies—short-term assistance for new tenants, a flat-rate lease, and buyouts for longer-term tenants—that could significantly increase the turnover in New York public housing units. Not only would this make more units available for those on the waiting list, but it would also help change the culture of the authority by encouraging upward mobility rather than long-term dependence.

NYCHA Today

New York City’s Housing Authority does little to ensure that its scarce public resources are fairly shared. Despite a shortage of units, NYCHA residents can stay indefinitely. Nor do residents face pressure to leave when they rise out of poverty. More than one in 10 NYCHA households have incomes greater than the New York City median ($53,000). Meanwhile, some groups are sharply underrepresented. Asians, for instance, account for 11.1% of the city’s households in poverty but make up only 5.1% of NYCHA households. In contrast, African-Americans constitute 25% of the city’s households in poverty but 45.5% of households in NYCHA. Hispanics, too, are overrepresented in public housing, constituting 33% of poverty households but 44.6% of NYCHA households.[5]

Tenants have a disincentive to increase their earnings while in public housing. By rule, tenants pay 30% of income as rent; as their income increases, so does their rent—in sharp contrast to private-sector tenants who sign fixed-term leases, which set a fixed rent. Between January 2018 and January 2019, 83,216 NYCHA households experienced a rent increase of $112, or 22% on average. Their rent increased, on average, from $519 to $631 as their income increased 16% ($4,271), from $26,019 to $30,290. For the same reason, some tenants have an incentive to earn less or to simply underreport income. During the same period, 43,730 NYCHA households saw their rent decrease by $160, or 27% on average. The average income for these households decreased 18% ($4,640), from $26,012 to $21,372.

If tenure in public housing were shorter, prospective tenants would not have to wait as long for housing, and more New Yorkers would get the help they need. Implementing such a policy, however, would require a change in public housing culture—from an open-ended time commitment on the part of the city to a form of transitional, “up and out” housing that encourages upward mobility. There is promising precedent for such an approach and a series of ways to realize it. Other public housing programs have implemented pilot programs designed to increase choice for new tenants, speed up turnover, and decrease wait times. The most promising approaches are short-term assistance for new tenants, a flat-rate lease, and buyouts for longer-term tenants.

Fixed Rent and Short-Term Lease Assistance

Not all public housing authorities offer assistance for an unlimited period of time. A federal program called Moving to Work (MTW), begun in 1996, allows local housing authorities to experiment with new rules to help tenants become self-sufficient. Congress allowed 39 public housing authorities across the country to offer a voluntary set of terms for new tenants.

Short-term assistance: Housing authorities granted flexibility by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) may offer new tenants, on a voluntary basis, priority admission if they agree to a time limit as public housing tenants. Public housing authorities have adopted time limits ranging from three to seven years.

Flat-rate rent: Under the MTW program, tenants in public housing can pay a fixed rent rather than 30% of income. This removes the disincentive to increase earning while in public housing and would be an inducement to save and increase income in preparation for a successful exit.

The short-term assistance model, coupled with “case management” services such as financial counseling, has shown an association with increased household income, diminished public assistance payments, and even “early exit” (before the agreed-upon time limit). Notably, the Housing Authority of San Bernardino, California, where the short-term-assistance (five years) approach has been in effect since 2012, has found that, over the five-year period, participating households saw their incomes increase by 12.8%, while the number with full-time jobs increased by 19.3%. During the same period, 17.8% of households obtained vocational program degrees. In addition, a significant percentage (27.9) had left public housing by the end of year three, two years before the five-year limit.[6] For the city’s housing authority, the program offered a way both to encourage household financial self-sufficiency and to make more of its limited number of units available to new tenants.

There is reason to believe that New York public housing tenants would welcome such a program. A significant number (20%) of tenants already exit NYCHA by the end of year five, and even more (36%) by the end of year 10—even without the incentives of an MTW approach.

Those numbers are reflected in Figure 1, which shows how many tenants are still in NYCHA housing among those who entered in 2009 and 2014.

Those numbers are reflected in Figure 1, which shows how many tenants are still in NYCHA housing among those who entered in 2009 and 2014.

In 2015, Congress expanded MTW to 100 additional housing authorities. Although the expansion was limited to “high-performing,” relatively small authorities, NYCHA could seek federal permission to pilot MTW in a small but diverse group of developments, particularly those with large numbers of units, with the goal of increasing the number of units available for households on the waiting list. The potential benefits are evident: doubling the five-year turnover rate for NYCHA as a whole would make more than 1,000 additional apartments available; doubling the 10-year rate would make 2,631 additional units available. Making a unit available that would otherwise be occupied has the same effect as building a new unit, but at a much lower cost.

A flat-rate rent program would not be entirely new for NYCHA. In 1989, the federal government gave housing authorities the flexibility to set flat rents. But it did so to provide an incentive for higher-income public housing tenants to remain, rather than as a way to help lower-income tenants save. After Congress set rent payment for public housing at 30% of income in 1968, housing authorities, including NYCHA, saw revenue decline, which made upkeep difficult. For higher-income tenants, 30% of income could be more than the rent for a similar-size apartment in the private market. Because these high-income households provide an important source of housing authority revenue, Congress decided to allow them to pay a flat rate.

At the height of the flat-rate rent program, in 2006, some 54,000 NYCHA households—roughly a third of all those in the system—paid a flat rent, with amounts divided into three tiers for those of different income groups (60% of area median income [AMI] or less; 60%–80% of AMI; and 100% or more of AMI). In 2014, federal regulation changed, in response to reports that some very high-income households lived in public housing. This prompted Congress to require that any flat rate must be equivalent to the HUD-determined “fair market rent” for a metropolitan area. Adjusting the rent based on income was no longer permitted. This led to a significant rent increase for flat-rent payers—and the number of such NYCHA households declined sharply. As of 2019, only 9,500 such NYCHA households remained.[7]

Nonetheless, the program sets a precedent: flat-rate rents, designed to minimize the work disincentive of a percentage-of-income-based rent, have been part of public housing. Such rents have not, however, been historically aimed at lower-income newly admitted tenants. This is exactly what NYCHA should seek permission from HUD to adopt—in conjunction with a tenancy time limit, both agreed upon at the time of admittance. The combination of a fixed-rent earnings incentive and the time pressure of a tenancy limit would encourage an up-and-out psychology for new tenants, offering the promise, at the same time, of a changed and healthier culture for NYCHA.

Rental Assistance Demonstration Program and Voluntary Tenant Relocation

The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program allows public housing authorities to attract private capital for renovation and, importantly, provides affected tenants with a Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) to help them find housing in the private market.

RAD is the most ambitious federal program to improve the physical condition and management of public housing. The program converts general financial operating assistance to a guaranteed rent subsidy (housing voucher) for each apartment in a complex included in the program. Because this revenue stream is guaranteed by Washington, private developers can borrow against it to raise funds for renovation. After doing so, the improved public housing is still technically owned by the housing authority, but it is privately managed. The housing authority’s role becomes that of quality monitor rather than owner-operator.

NYCHA has applied for authorization from HUD to include 7,725 units in 64 public housing developments in the RAD program. RAD’s emphasis on bringing private capital and management methods to bear on public housing would benefit NYCHA, which has been plagued not only by limited funding but by deep management dysfunction, as described in compelling detail by the federal monitor.[8]

RAD allows current public housing tenants whose developments are converted to obtain an HCV, which pays the difference between 30% of their income and the full rent and gives some tenants a housing subsidy they can use to relocate elsewhere in the United States. As HUD explains to tenants who have the voucher,

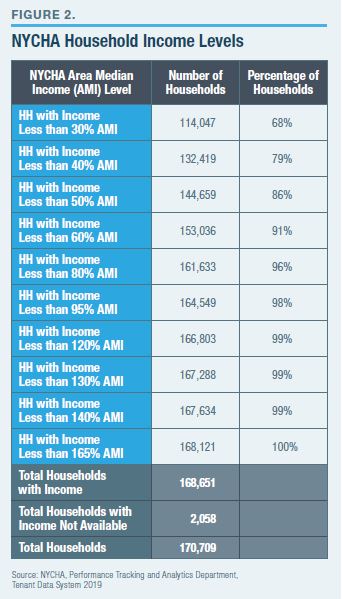

All public housing tenants in a RAD building have the right to remain in their apartments. The “portability” option is open only to those who are not “over-income”; that is, they must qualify anew as low-income households. This would not likely prove a major obstacle for NYCHA tenants, some 68% of whom earn 30% or less of the New York area’s median income (Figure 2).[10] (Voucher holders may, however, earn as much as 80% of area median income and still qualify for the program.)[11]

All public housing tenants in a RAD building have the right to remain in their apartments. The “portability” option is open only to those who are not “over-income”; that is, they must qualify anew as low-income households. This would not likely prove a major obstacle for NYCHA tenants, some 68% of whom earn 30% or less of the New York area’s median income (Figure 2).[10] (Voucher holders may, however, earn as much as 80% of area median income and still qualify for the program.)[11]

As part of its approach to RAD, NYCHA should make clear to current tenants that they have the option—but, of course, not the obligation—to relocate, either elsewhere in the city or to another part of the United States. Some may want to be nearer to family located elsewhere; others may pursue economic opportunities. Should even 10% of households in RAD projects decide to relocate, that would mean the turnover of more than 700 units, the size of a significant new affordable housing development. Were RAD to be used to redevelop additional NYCHA developments, that figure could, of course, increase. To the extent that tenants in some units have been over-housed, new households could be larger and thus NYCHA could serve a larger population.

Another factor to be considered is that some 62,000 New Yorkers currently reside in city-financed housing shelters. Greater turnover in the city’s public housing system, facilitated via RAD, will diminish the need for such shelters—and provide, at least in theory, better accommodations in which to raise children.

Tenant Buyouts

Not all NYCHA’s 316 housing developments are likely to be covered by the Rental Assistance Demonstration program. For those that are not, it is worth considering other ways to encourage tenants, especially the over-housed, to exit in a manner that they voluntarily choose. It is important to note that conditions in many NYCHA buildings are so substandard—as a result of mold, water leaks, and rat infestations—that the federal monitor overseeing the system has suggested that some tenants be relocated to trailers provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Given these conditions, many tenants would likely welcome any incentive to leave.

Figure 3 makes clear the mismatch between households on the NYCHA waiting list and the available NYCHA inventory.

NYCHA could offer tenants a buyout: a one-time payment to tenants willing to exit and who choose to accept it. By conducting market research among current tenants, NYCHA could get a sense of which types of tenants would be most interested in a buyout and approximately how much money they would be willing to accept. NYCHA would also have to decide whether its goal was to make as many units as possible available through this approach, or whether to target over-housed households, many of them elderly. NYCHA could, alternatively, seek to concentrate exits to facilitate repairs and improvements in specific developments, or to reconfigure its existing stock of housing. The authority has long expressed frustration that the largest number of its units (50%) have two bedrooms, notwithstanding demand for both smaller and larger apartments. A vacant building could be reconfigured to increase the number of units with more bedrooms. If the appropriation were annual, the number of available units would steadily grow, making renovation easier. The authority could even focus on maximizing exits from buildings located on valuable real-estate sites, with an eye toward selling those properties to realize revenue for improvements in other properties. Such “relocation assistance” would have to be limited to whatever pool of funds NYCHA could either divert from other purposes or obtain for this goal, whether through federal, or even philanthropic, support.

Even a relatively small $50 million relocation fund could make a big difference. (For context, NYCHA currently spends $30 million a year on “sidewalk sheds,” which cover building entrances to protect tenants from debris that might fall from decaying facades.)

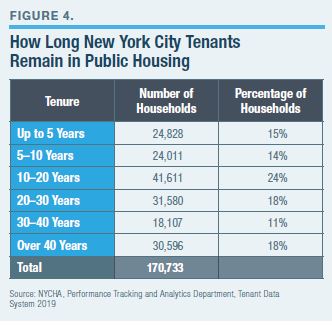

One cannot know with any certainty who would be most likely to take what might be called a “buyout.” Thus we must model some assumptions. NYCHA would likely compensate tenants based on the number of years they have lived in public housing (Figure 4). If NYCHA were to offer $2,500 for each year a household has been in public housing and the average tenure for those accepting the offer were 20 years, then the average exiting tenant would receive $50,000—and 1,000 buyouts could be financed. Alternatively, if the buyout offer were $1,000 for each year in public housing and the average tenure remained 20 years, the average buyout would be $20,000, and 2,500 tenants could be served.

One cannot know with any certainty who would be most likely to take what might be called a “buyout.” Thus we must model some assumptions. NYCHA would likely compensate tenants based on the number of years they have lived in public housing (Figure 4). If NYCHA were to offer $2,500 for each year a household has been in public housing and the average tenure for those accepting the offer were 20 years, then the average exiting tenant would receive $50,000—and 1,000 buyouts could be financed. Alternatively, if the buyout offer were $1,000 for each year in public housing and the average tenure remained 20 years, the average buyout would be $20,000, and 2,500 tenants could be served.

Even were a smaller number of households to accept such a buyout, the numbers would still be significant. In effect, each vacancy creates an affordable housing unit that would otherwise not be available. New construction of such units is costly. New, affordable units located in the mid-Atlantic region and whose construction is financed with the federal low-income housing tax have been found to cost an average of $233,000 per unit to build, with costs ranging as high as $292,000 per unit.[12]

Making Change Voluntary

Of course, many will worry about the housing prospects for tenants enrolled in a time-limited program who are forced to leave public housing. In San Bernardino, many families enrolled in the program have fared well upon exit. Admittedly, positive results in a small city may not scale, but there are several reasons to believe that New York could achieve similar success, at least if the program were implemented on a trial basis in select NYCHA developments.

1. Voluntary enrollment: As in Moving to Work programs elsewhere, enrollment in a flat-rent/time-limited lease arrangement should be a choice, not a mandate. Those willing to enroll should, however, be given preference on the waiting list, assuming that they meet all required income qualifications such as income, number of children, and other dimensions of need. Prioritizing those who accept a time limit will help increase the overall availability of NYCHA units, but no one should be forced into the program.

2. Post-NYCHA housing: Those who do enroll in the program will minimize their public housing rent and have a chance to accumulate savings, but some households may still have difficulty finding private housing upon exit. However, there are several ways to alleviate this problem.

First, it’s important to note that because NYCHA rent increases with income, the difference between public housing rent and market rent is not as great as one might think. For instance, a household earning $48,240 annually is required to pay $1,206 per month in public housing.

Second, there is more housing for people of modest means available in New York City than is generally appreciated. In my 2015 paper with Alex Armlovich,[13] we found that many people with incomes eligible for subsidized “affordable” housing would be able to rent an unsubsidized apartment on the private market. As we noted, affordable units can be found

To ease the transition for those approaching a NYCHA time limit—and, as a general rule—NYCHA should develop partnerships with online apartment search services such as StreetEasy or Localize to provide guidance as to specific available apartments within the income range of those who have chosen the time-limited/flat-rate option.

Most importantly, the guiding principle of this approach is upward mobility. We should encourage those in public housing to increase their incomes while receiving assistance, rather than expecting them to remain dependent for the long term.

Conclusion

All the proposals discussed here would help increase the turnover in public housing, providing help to more people who need it. But the underlying goal is broader and more ambitious: transforming the character of the city’s vast public housing system.

NYCHA has fostered a culture of long-term dependency—nearly half of all households in public housing have been there for 20 or more years. Many NYCHA developments are so isolated and concentrated that they have come to resemble reservations for the poor—predominantly, poor people of color. The current system disincentivizes earning more money, which is necessary for upward mobility. Further, those in public housing cannot accumulate real-estate assets while living in government-owned housing. Indeed, the system encourages multigenerational poverty—family members can, in effect, pass their units on to younger family members by placing several names on the apartment lease. Some effects are more subtle. NYCHA households are encouraged to turn to an inefficient bureaucracy to deal with the sorts of maintenance issues that homeowners must learn to handle for themselves. Public housing is not just apartment living—it is an institutional life.

The three major proposals in this report—a short-term-assistance approach for new tenants, a flat-rate lease, and buyouts for longer-term tenants—would help turn New York’s public housing system into a launch pad for upward mobility. Its essential nature would be transitional, a way station for tenants as they increase income and acquire job skills. The authority would have to do its part in renovating and maintaining the aging properties. But a NYCHA filled with striving families, encouraged in their efforts, would be a healthier overall environment.

Endnotes

- U.S. v. New York City Housing Authority, 347 F. Supp. 3d 182 (S.D. NY, 2018).

- New York City Housing Authority, “NYCHA 2019 Fact Sheet,” March 2019. NYCHA maintains two waiting lists: one for admission to public housing and one for Section 8 vouchers, which provide subsidies for rental housing in the private market. As of March 2019, there are 138,705 applications on the waiting list for Section 8 vouchers.

- HUD, A Picture of Subsidized Housing.

- NYCHA Performance Tracking and Analytics Department, Tenant Data System, January 2019.

- Ibid.

- Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino, “Term-Limited Lease Assistance Program: Summary of Outcomes from Year 1–5,” April 2018.

- Tenants who previously paid a flat rate did not necessarily move out after the policy changed. Many had their rents increased to 30% of income and then remained in NYCHA housing.

- Bart M. Schwartz (federal monitor), “Monitor’s First Quarterly Report for the New York City Housing Authority Pursuant to the Agreement Dated January 31, 2019,” April–June 2019.

- HUD, “RAD Fact Sheet #9: Choice Mobility.”

- NYU Furman Center, “Fact Brief: NYCHA’s Outsized Role in Housing New York’s Poorest Households,” The Stoop (blog), Dec. 17, 2018.

- Erin Eberlin, “You Must Meet These 4 Requirements to Receive Section 8,” The Balance Small Business, May 31, 2019.

- Abt Associates, “Variation in Development Costs for LIHTC Projects,” prepared for National Council of State Housing Agencies, Aug. 30, 2018.

- Howard Husock and Alex Armlovich, “Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing in New York: The Surprising Extent of NOAH,” Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Oct. 20, 2015.

- Ibid. Admittedly, because most NYCHA tenants do not pay for electricity or gas, the costs associated with renting an apartment on the private market would be somewhat higher, even if rent were comparable.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).